A Tale of Two Insomniacs

On death, dying, and the fear of the unknown

It is mid-January and the temperatures are well below zero. I have woken up because I am cold, because the full moon reflecting off the white snow is making my bedroom daylight-bright, and most of all, because I am anxious. I toss and turn and wake up a few hours later exhausted. I am the opposite of well-rested.

The day goes by in a blur. I go through the motions at work. I am physically there, but my mind is racing in circles. I leave for the day feeling ashamed, knowing full well that I did not give my best to the patients I worked with today. I decide to stop to visit Ray, a former-patient turned friend, who lives in a facility that’s on my way home. I know this will cheer me up.

Ray and I bonded over our love of food and dogs and history. When he moved on from the facility that I work at and transitioned to hospice care, his wife was adamant that we exchange contact information so we could stay in touch. I am glad she did because visits with Ray have become a balm during this anxious time in my life.

I knock on the door to his room and find him nodding off in his wheelchair. I ask him how he slept the night before. This is a question I ask all the patients I see, and even though he is no longer under my care, old habits die hard.

Ray tells me that he woke up multiple times in the middle of the night, gasping for breath like a fish out of water. He calls them his “episodes.” He describes the panic he feels when he can’t catch his breath, how the minutes between when he pushes the call button to ring for his hospice nurse and when she finally arrives with a steroid nebulizer seem to stretch on forever.

I gauge how well Ray is doing by the number of words he can speak before he becomes short of breath. Today is a good day—he speaks in full sentences before he gets winded. He offers me a cream soda from the mini fridge in the corner, and I sit down on the seat of his rollator walker, with my elbows on my knees, leaning in close so I can hear him over the noise of his oxygen concentrator.

Today Ray tells me a story from his childhood, how he used to hang onto the metal fenders of cars to hitch rides to places in the winter, his feet sliding on the ice. “One time, I didn’t let go fast enough and I got hit by another car. My body was black and blue. My brother and I snuck me into the house so my parents wouldn’t find out. They eventually did though. There was no way to hide that, but we had to try!”

Ray is long-winded and he gets dry mouth easily because of his disease and side effects of some of his medications. He stops intermittently to “wet his whistle” as he says, taking small sips from a bottle of water that he clutches with two hands. He is extra shaky today, so I help him get the bottle to his lips so he doesn’t spill.

“Enough about me! How are you? Are you getting excited for the big trip?” He asks me with a big grin.

Ray is referring to my trip to Colombia with my husband that is just over two months away. I’ve told him all about Ben’s chronic pain, how his dad is funding our trip to a medical facility where Ben is going to get a stem cell procedure done that will hopefully reduce the pain he’s been living with for years.

I answer Ray honestly. “I am not excited yet. I’m mostly anxious. I am worried about my dogs, how they are going to do without either of us. I am worried about the amount of pain Ben is going to be in when we travel. The only recent flying I’ve done has been to Nebraska and I am worried about what traveling abroad is going to entail.”

Ray pats my hand. “You’ll be just fine! Think of the food you’ll eat! Think of the stories you’ll bring back with you!”

Ray tells me another story from his younger years, and I try my best to be present. I smile and nod my head to show that I am listening. I try not to panic thinking about my upcoming trip. “Be in the NOW. Never Over-Whelmed.” I repeat this phrase over and over in my head, a mantra of sorts. I don’t know where I heard this from—my friend Lynn who is a therapist or a book by Brené Brown or maybe a meme on Instagram? Who knows. It helps momentarily, and I’m able to get lost in Ray’s story.

As the weeks pass, my anxiety grows and so does Ray’s. “What do you think happens when we die,” he asks me one day out of the blue.

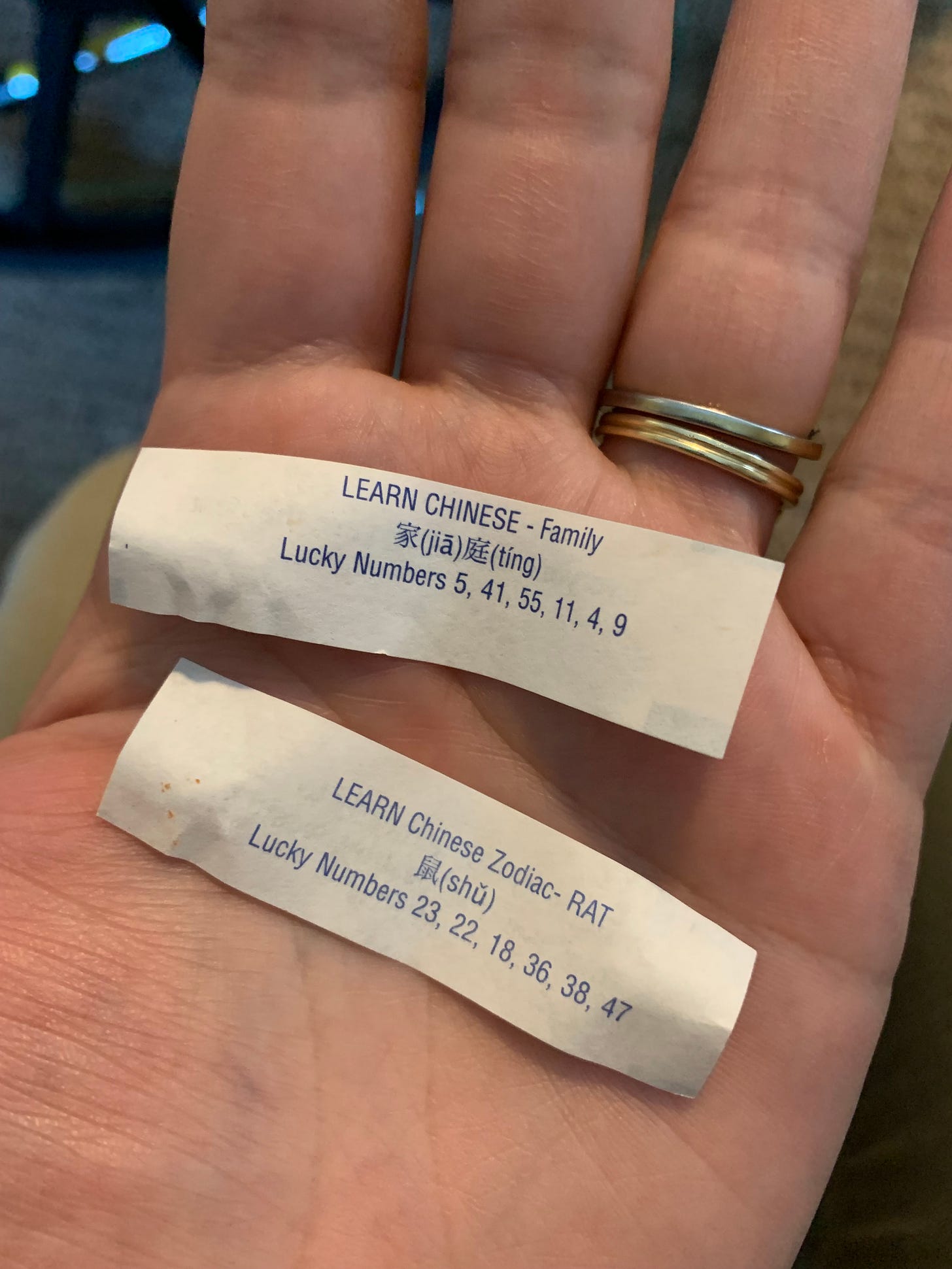

Ray has been a devout Catholic his whole life and still receives weekly communion. He is well aware that I am agnostic at best. I know that there is no answer that I can give that will reassure him, so I try the next best thing—to make him laugh. “I’m not sure, but if you find a way to communicate from beyond the grave, I would appreciate it if you told me the winning numbers for the lottery.” We both laugh and the topic is changed, and we carry on with our visit as usual.

The next time I see him, Ray tells me that he has my lottery numbers. He hands me two slips of paper from the inside of fortune cookies. “I told my wife to buy tickets, but she won’t do it.” I tell him that I’ll buy them and if we win, we can split it 50/50. We shake on it. I notice that his lips are more purple today than before, that the wheezing in his chest is louder. I ask him if he is uncomfortable, but he says no. “They got me on morphine now, so I don’t feel much.” I think of how this is a blessing.

Ray asks me again about my thoughts on the afterlife. “I just don’t understand why God would put me in this position. There has to be a reason, right? There has to be some reason the Big Guy is keeping me around.”

There is no rhyme or reason for most everything. We can try to make sense of life’s events, but most are random. I like to think that the universe conspired so that I could meet Ray, but I know that it’s all chance. I don’t tell him this, instead I redirect him by changing the subject. We talk about all of the golden retrievers he had throughout his lifetime. We talk about our hometowns, and I’m surprised to learn that he has traveled to mine. He tells me he visited the arboretum in Nebraska City when his kids were young, and he begins to describe Arbor Lodge to me like it is one of the seven wonders of the world and not a 74-acre plot of trees bordered by cornfields and flatlands. He is right though, it is a beautiful space, and hearing him describe it with such awe makes me yearn for my hometown. I’ve been to Arbor Lodge hundreds of times, have posed for so many family photos there, but I don’t tell Ray. I want to see it anew from his memory.

Soon I grow tired and weary, and I begin to yawn. I apologize to Ray, tell him that I haven’t been sleeping too well and he tells me he hasn’t been sleeping well either. “I can’t turn my mind off. I’m worried about what happens next,” he says. I think of how we are one in the same.

I can’t sleep because soon I’ll be in Colombia so my husband can get stem cells injected into his back that may or may not help alleviate his debilitating pain. Ray can’t sleep because he is dying. The fear of the unknown is keeping us awake at night.

Weeks pass and my appetite becomes nonexistent because of anxiety. One morning after a fitful night of sleep, I wake craving something sweet and decadent. I want a gooey caramel roll from my favorite cafe, but I know that a whole roll will destroy my stomach since I’ve been eating mostly vegan the past few weeks. (My husband has to be on a special diet for his procedure and I’ve been participating begrudgingly in solidarity.) So, I get a roll to-go and take it with me to visit Ray.

When I arrive, he is sitting near the window. On the floor next to him is a yellow coffee mug broken into pieces. “My hands were shaking too bad. I knocked it over when I set it down.” He tells me this, two words at a time, his breath coming in short gasps. I ask him if he needs a nebulizer, and he shakes his head yes.

While we wait for his nurse to arrive, I cut the roll in half. Ray waves his hand at me. “You better cut my half in half,” he laughs, “I’m trying to watch my figure.”

I scarf down my portion of the roll while he tentatively takes a bite. “This is really good! I’m going to have to tell my wife about it,” he says in between bites. We talk about the food I’m going to make over the weekend, and he makes me promise that I’ll bring him an enchilada one of these days to try. He tells me that the food at his facility is hit or miss, that he misses the pasta his Italian mother used to make for him. I gather my stuff to leave and can feel the anxiety radiating off of him, and I wish I could stay longer but I have to get back to work.

“Thank you for coming. These visits mean so much to me,” Ray says and reaches out for a handshake.

“Ray, these visits mean so much to me! Is it okay if I give you a hug?”

He nods his head and I crouch down to embrace him, trying my best to avoid pulling the oxygen tubing from his nose. “I’ll see you next week! You’ll have to tell me about that time you saw a UFO.”

“Yeah, remind me to tell you that story! It’s a good one!”

That weekend I sleep little. The trip is now two weeks away and my brain is spiraling in anxiety with all of the ‘what ifs’. It snows 17 inches and the clocks spring forward. Monday morning comes and I am a zombie. After I shovel the deck, I take my dogs for a walk, and they immediately run off into the woods. I chase after them in waist-deep snow and grow so exhausted, I have to flop on top of the frozen snow and barrel roll until I am back on the packed ice of the trail. The dogs find their way back a few minutes later and I laugh because I know this will be a good story to tell Ray.

I go into work and am busier than I anticipated, and then I get called into my part-time job. It’s nearly dinner time when I finally clock out. I decide I’ll visit Ray the next day. When I get back home, I finish the last bit of shoveling and when I’m done, I take my phone out of my back pocket to check the time and see that I have a voicemail from an unknown number.

I listen to it and the first few seconds are guttural sobs, before finally words are spoken. “JoVanna. This is Ray’s wife. Unfortunately they found Ray in his recliner unresponsive this morning. He’s gone.”

The message ends with more sobbing and then a request to call her back. When I do, she is surprisingly calm. We talk about how wonderful of a guy Ray was and of his storied life. When I ask about service arrangements, she tells me that there will not be a service. Instead, Ray wanted to use that money to start a college fund for local kids. Ray was a true mensch like that, selfless to the end. She ends the conversation by saying, “You’re one in a million, kid. Your presence made such an impact on him. You meant the world to him, and he loved your visits.”

I feel no grand emotions. I am used to multitudes of deaths in my career. I am selfishly sad that I won’t have visits with Ray to distract me from my own anxieties, that I won’t get to hear the story about the UFO or any of his other tales. I’m sad that Ray never got to try my gorditas or enchiladas. I was foolish and thought we had more time, even though he had a terminal illness. I was foolish and thought that he would be there when I got back from Colombia, grinning and eager to hear about my adventures.

The next day I drive by Ray’s facility, and I break down in tears. Sometimes grief is delayed.

Ben and I leave for Colombia ten days later and narrowly miss our first flight. I remain cool, calm, and collected despite my entire being wanting to run out the door of the airport and all the way back home. Breathing in through my nose and out through my nose, I will my heartbeat to slow down. I say silent requests not to a higher power, but to my old friend. If there is a heaven, surely Ray is there, surely he will make stars align so that we get to Colombia on time and unscathed.

Most of the day goes swimmingly. I rub Ben’s back and tell him dumb jokes during our long layover in Minneapolis, trying to distract him from his pain. We watch movies on the flight to Atlanta sharing a pair of headphones like Jim & Pam from The Office. We spray our stinky armpits with tester bottles of cologne at a fragrance store in the airport, and we stretch our legs by walking laps around our boarding gate. On our flight to Bogotá, we scarf down chicken salad sandwiches that taste impossibly delicious to our deprived taste buds. Our anxiety has lifted enough for us to have appetites again.

When we land in Bogotá, we discover that the international phone plans we purchased are not working. We move to the side so we don’t obstruct foot traffic and log onto the Wi-Fi so we can let our friends and family know we’ve made it to Colombia and are one flight away from our destination. When we look up from our phones, there are hundreds of people in front of us. The line for immigration and customs spills out into the hallway. We have just over an hour and a half before our next flight departs. We have just over an hour and a half to make it through this massive line and through customs, through the airport and to our departure gate.

We scurry onto the automatic walking pad to join the line, but an immigration worker blocks it, and we are forced to walk backwards so we don’t knock over the people in front of us. Distress is written on everyone’s faces, and she finally stops the pad, asking every person one-by-one if they have any items they need to claim before entering the country. Soon enough we are in the actual line for customs. We have just over an hour until the last call to board our flight. I tap my chest with a closed fist over and over again. The internet told me that it helps with anxiety, but for me it is fruitless. I am terrified that we will miss our flight, that we will be stranded in Bogotá.

The line moves slowly and the stress from other travelers is palpable. People start to groan as they realize their flights are departing without them. Finally, it is our turn to go through customs. I apologize to the woman working, tell her my Spanish is not the best. She asks why we are going to Colombia, how long we will be staying. She wants to know what I do for work, how I know Spanish, the address of our hotel. I answer all of her questions as best as I can, and then I ask her where I can find my departure gate. She describes the route to me, speaking in rapid-fire Spanish, and I piece together some semblance of directions with what I’ve comprehended. She asks me when my flight departs, and I tell her in 40 minutes. She must think I’ve said the wrong time, so she takes my ticket to verify for herself. Her eyes widen, and she repeats the directions to my departure gate. She hands me my ticket and says, “Corre, corre, corre.” Run, run, run. And we do.

We have to recheck our luggage after going through customs. Finding our gate is easy, finding where we need to check our bag proves to be harder. I ask a few people for help and eventually find the way. We go through security and make it to our gate with minutes to spare. We are exhausted, and Ben is in excruciating pain. But we made it, we are on the final stretch of our trip.

We land in Medellín and navigate our way to the baggage claim, only to find that our baggage is not there. Ben locates our driver, and he helps us find an airport employee to assist us with filling out a form for lost baggage. I am grateful that we packed an extra outfit in our carry-ons, that our hotel is joined to a shopping mall if our bag ends up being lost forever.

It is pitch black outside and the roads through Medellín are winding. Motorbikes weave between cars, traffic laws seem to be innate and nothing like those in the States. I clutch the door handle and stare out into the darkness.

Checking into the hotel is a breeze and when we get to our room, we are wired with adrenaline from our travels. We take showers, washing away the grime from the day. We chug the waters and passion fruit flavored Gatorade from the fridge in the room, not bothering to look at the price, just happy to quench our thirst. We eat granola bars from home before finally crawling under the covers.

I sleep the best I have in weeks, and wake after only a few hours because my phone is vibrating on the nightstand. It is the airline calling me on Whatsapp to tell me that they have found our lost luggage and will deliver it. There is no way I am falling asleep again, so I get out of bed and draw the curtains. I am greeted by the sight of barely visible mountains cloaked in dense fog. It feels surreal to finally be here.

The rest of the trip is a blur of medical consultations, IV drips, and therapy appointments for Ben. I roam the mall while he is busy, and I make it my mission to try as many desserts as I can. We go on a tour of Comuna 13 and are smitten with the street food. The next day Ben has stem cells injected into his spine, and during the procedure I sit by the pool on the rooftop with a book. I soak up the sun and the views of the city, trying not to worry about Ben. When he returns to the hotel room, he is nauseous from anesthesia and sore from the injections. I find a drug store in the mall and scan medicine labels until I find one that might help. The last day we get our first ever massage, and we giggle at the awkwardness of it all. We order room service, and we count down the hours until 3 a.m. when our driver will arrive to take us to the airport to start our journey home.

Traveling back to the United States is mostly uneventful. Ben feels surprisingly okay despite the long travel day, a testament to the stem cells perhaps. Everything is going well until we board our flight to Duluth, only for it to get canceled at the last minute. I think I jinxed it by saying “Oh what a long day, it’s going to be good to be home!” as we boarded the plane.

There are no other flights we can take that night or the next day. We learn that all the rental cars are long gone. I cry in the airport from exhaustion, and because I’m sad that I’ll spend another night away from my dogs. We would’ve been stranded if not for the fact that our friend from Duluth just happens to be in Minneapolis. He picks us up and we stay with him at his sister’s house, a very sweet woman we’ve never met who lets us sleep in her bed and says, “I have always wanted to sleep on the pullout couch in the sunroom.” It is all so kind.

We sleep a few hours before we pile into our friend’s truck for the journey to Duluth. We are tired and smelly and thankful for the kindness of others, that we are finally on our way home. We get dropped off at the Duluth airport and have to jumpstart our car, one last hurdle to cross. We say hello to the eagles and deer that we see on our drive up the shore, tell Lake Superior how much we’ve missed her. We open the front door to our dogs who buzz around our legs, jumping up to lick our faces. It feels so good to be home.

Days pass, then weeks, and soon an entire month. Ben begins to feel a little bit better with time. He still has pain, and some days are worse than others. It takes three to six months before he will start feeling the full effects of the stem cells, with progress continuing for over a year. Time will tell, but for now we are living in the unknown, in a limbo of sorts. Anxiety about what the future will bring is ever-present. But we are hopeful.

Ray’s been gone for two months now. I think about him at least once a day, usually when I eat something especially delicious or when my dogs do something silly that I know would’ve made him laugh. I can’t tell him face-to-face about my adventures in Colombia and my current anxieties about not knowing just how successful the stem cells will be for Ben’s back pain. So I’m doing the next best thing–I’m writing it all out in hopes that the words will make it to him somehow. If you’re reading this Ray, I miss you and I’m still waiting for those winning lottery numbers :)

This was so beautifully written. 🖤