"Do you guys ever think about dying? -Barbie™" -JoVanna, a healthcare worker

Notes on Barbie™, burnout, and existential dread /// plus a few melancholic book recommendations

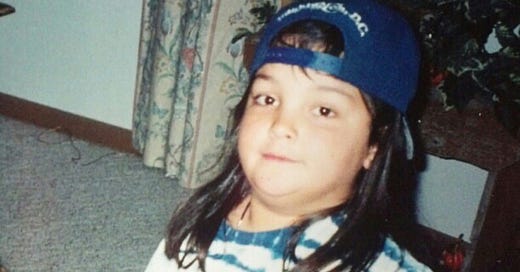

As a child I stayed entertained by my vivid imagination, spending lots of time in my own head. I would make up games to play with my siblings, spent many afternoons putting on silly skits trying to get them to laugh. I’d tell ridiculous long-winded stories during car rides. The only doll I ever really played with was a cloth Woody™ figurine from the movie Toy Story™, and that was only because of my infatuation with the movie and the concept of benign toys coming to life.

I had no interest in dolls or anything I perceived as girly for that matter, so I was surprised when my mom got me a Barbie™ doll for Christmas when I was 7 or 8. This particular Barbie™ wore a mesh jersey and held a basketball in the crook of her arm. My mom thought the addition of sports to the doll would make it more appealing to me, but I mostly played with the plastic basketball instead.

I could never relate to Barbie™ with her sleek blonde hair, flawless skin, thin torso and equally skinny limbs, her manicured nails and clothes that fit just right. I was a tall and chubby tomboy, with thick dark hair and broad shoulders, dirt under my fingernails and clothes that never seemed to fit just right. If anything, staring at the plastic face of Barbie™ made me too aware of the ways in which I was different from most girls my age.

And yet, over twenty years later, I suddenly find myself resonating with Barbie™, not because our looks have changed dramatically or because I’ve suddenly taken an interest in more feminine things. No, it’s because apparently we are both preoccupied with the concept of dying.

Hi, Barbie! I think about dying all the time! It’s not because I am terminally ill or dangerously depressed. No. It’s because I work in healthcare, baby! Specifically I work in long term care facilities, a setting where I witness death and dying and the slow decline of people every single day.

Long term care facilities is a euphemism for nursing homes. It is the end of the road for many. They find themselves living at these facilities for a variety of reasons—they need too much assistance to complete the daily activities needed to stay alive and can no longer care for themselves at home, or they are confused and pose a safety risk to themselves, or they’ve been strong-armed into moving to a facility by their children. No matter the reason, they are all grieving the loss of life as they knew it.

I try not to think about dying so much, but it’s impossible. I go to work and my boss greets me by listing off names of people who’ve passed away over the weekend. The first person I evaluate tells me that his daughter just died in February, and he has just found out that he has terminal prostate cancer. The next person on my list has a small, intricate clay container on his bedside table. At first glance I think it is a salt shaker and my curiosity makes me ask him what it is. He tells me it’s his wife’s ashes. He says he doesn’t like to be apart from her.

I waltz into the room of my next patient, singing a little jingle with her name in it because I can’t help myself. She gives me a sad lopsided smile, tells me she’s come to terms with the fact that she won’t be returning home after her stroke, that she will die in this room one day. The little old lady who has lived in the facility for the entire two years that I’ve worked there, the one who reminds me so much of my great-grandma Rose, dies suddenly and unexpectedly. I weep in my office upon hearing the news.

I read hospital reports daily, skimming them to gather pertinent information on the people I’ll be evaluating, and I am flooded with terms that hit too close to home—disc degeneration, spinal stenosis, radiculopathy of the lumbar region. I become nauseated thinking about what the future might bring for my husband, for us.

I do not fear death, but I am petrified of all the losses I’ll endure between now and then. If I’m fortunate enough to live a long life, I will lose a long list of family members and friends and companions. I stare into my dogs’ eyes every day and know that time is fleeting, that I will experience great grief over and over again. Loss lurks all around and my heart can hardly take it.

Hi, Barbie™! I am so tired of thinking about dying all the time.

*I have not seen the new Barbie™ movie yet, so no spoilers please :) I am very much excited to see the film, despite not being a Barbie™ fan as a child. I’m just waiting for it to be available to stream because I’m ballin’ on a budget. 😎

Summer is winding down in Northern Minnesota, but for many of you the days still feel long and the weather is warmer than ever. You are still venturing out to lakes and pools, and you might still be in the market for a good book to escape into while lounging on your beach towel.

Lucky for you, I have a few melancholic beach reads to recommend! Because working with people who are dying is not enough, I need to read about it in my free time 🙃

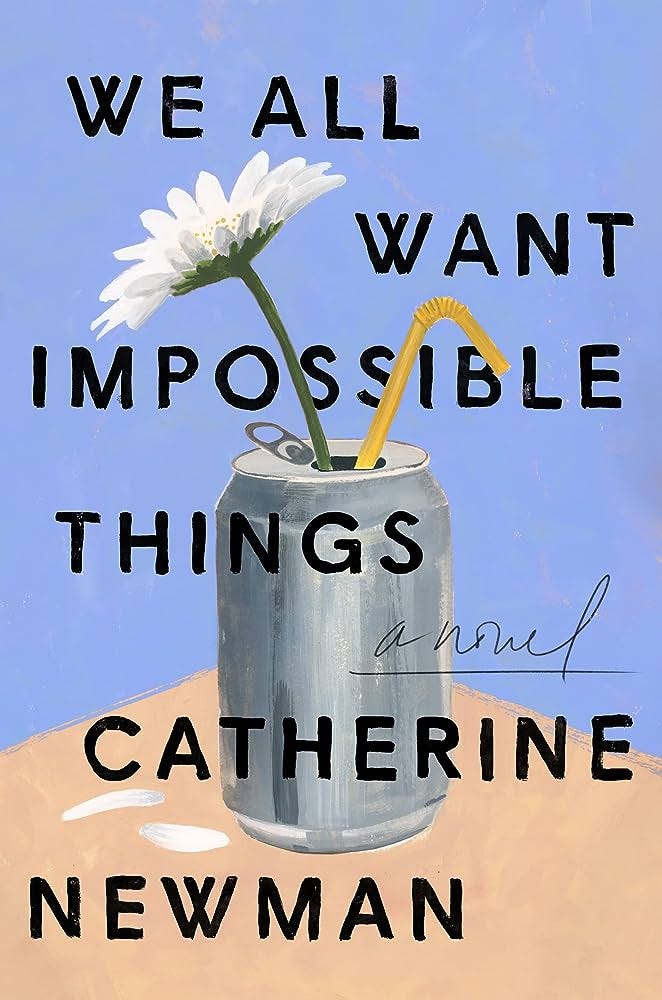

Catherine Newman’s novel, We All Want Impossible Things, is a book that largely takes place in a hospice care center. Edi and Ash have been best friends for over forty years, sharing many moments of their lives together including marriages and infertility and raising children. Now they find themselves sharing the last moments of Edi’s life when she is diagnosed with terminal cancer. CNAs, nurses, and palliative care workers are truly angels and this book does a great job showcasing the highs and lows of such work. It’s a sad book, but it’s also riddled with humor. The beauty of platonic friendships is honored throughout. I really enjoyed reading this book. “It’s monstrous. It is too much to take. Why do we even do this—love anybody? Our dumb animal hearts.”

A Living Remedy is the second memoir penned by Nicole Chung, who writes about the deaths of her adoptive parents and how better access to affordable healthcare could have prolonged their lives. This book makes you think about your own parents and family, their mortality, and how the love you hold for them will one day result in an equal amount of grief. The writing is so beautiful, the prose so light, that it turns a memoir about death and dying into a book you can’t put down. “How do you learn to cherish yourself, your life, when grief has made it unrecognizable? I am starting to feel that we do so not by trying to fill a void that can never be filled but by living as best as we can in this strange, yawning terrain our loved ones have left behind, exploring its jagged boundaries and learning to see it as something new.”

Annnnnd that’s all folks! Sorry this newsletter was a wee bit of a bummer. That’s just where my brain is at most of the time, and writing it all out is cathartic. I’m excited to share some news in the near future about some changes I’ve been making to help my ~mental health~.

If you enjoyed this newsletter and would like to support me further, may I suggest sharing Parallel Charts with a friend or foe with the recommendation to subscribe. As always, thank you for taking time to read this!

This newsletter is free to read, but it takes a lot of time and energy to make. If you’d like to financially support the sustainability of this little endeavor AKA buy me a coffee, feel free to send some coins via Venmo (username: JoVanna-Balquier).